3,800 words. Reading time: ~14 minutes.

Complete amino acid profile calculator included. Click here to jump straight to it.Article reviewed by scientific researcher of plant protein Victoria Hevia-Larraín.

Co-authored by Vincent Sparagna (Facebook) and Sten van Aken. Without their help, I’d still be stuck on the first sentence.

Are you a…

Flexitarian?

Vegetarian?

Vegan?

Or simply someone looking to eat less meat?

They all involve eating more plant-based foods, and eating more plants comes with questions: How do I get my protein in? How much protein do I even need?

Some want to know to stay healthy. Some want to know to attain eye-popping physiques.

Furthermore: how the hell are you going to manage that Bodybuilding BBQ party you host every year?

Welcome! This article is for all of you, and it will shed light into what you can do to optimize health, muscle growth, and awesomeness while eating (more) plant-based proteins!

First we’ll explain what proteins are made of (hint: amino acids), then we’ll explain the ‘problems’ with plant proteins vs. animal proteins, and finally we’ll bring it all together by offering solutions to overcome these, including a calculator and some meal examples.

We wrote this article in particular for the serious athlete that seeks to optimize their physique, fat loss, and performance. For general health, you don’t need such a serious approach to your nutrition.

Recently, Larraín and colleagues (2019) found that participants eating either a vegan or meat diet gained the same amount of muscle after 12 weeks (Tap), which is the first evidence that ‘protein quality’ may not be that important after all. However: it’s one single (unpublished) not-so-well designed study (Tap), and the theoretical support that protein quality matters for muscle growth is still very sound.

Present the evidence: hover on laptop or tap on mobile to see a citation or research image behind the claim.

Amino acids 101

Protein is made up of little protein building blocks called amino acids. Your body uses them for all types of things: to properly digest food, produce hormones, keep your brain running, etc. But most importantly: your body also uses these amino acids for muscle growth.

Not ingesting enough ‘essential’ amino acids – the ones your body cannot produce by itself – will likely limit muscle growth (Tap) [2] (Tap) [3] (Tap).

Since total protein intake from a ‘balanced’ omnivorous diet is basically equal to your total essential amino acid intake, the infographic below illustrates this.

As you can see, getting only 75% of the optimal amount of essential amino acids (protein) generally means a decrease in muscle growth by about 40% (Tap).

Moreover, you also need to eat enough protein if you’re trying to lose body fat. To protect your muscle mass. We’ll get to that later.

However, the above protein research is done on people eating a ‘balanced’ omnivorous diet, which contains mostly animal protein sources.

These protein sources contain amino acids, the building blocks for muscle building.

You could imagine your own body as an axe that cuts down a tree (food) and processes it into planks (amino acids) that it uses to create something useful, like a wooden door (muscle tissue).

However, some trees contain more ‘good’ wood than others. Similarly, not all protein sources are created equal. There’s a difference between animal and plant protein sources.

100 g of protein from beef doesn’t necessarily give you the same amount of essential amino acids as 100 g of protein from tofu.

Take-home messages:

- Amino acids are the building blocks of protein.

- Your body uses amino acids for different functions, including muscle growth.

- Essential amino acids are the ones your body cannot produce by itself: you have to get them from food.

- Not eating enough essential amino acids (protein) limits muscle growth or maintenance.

- Not all protein sources are equal: for example, some have less essential amino acids.

Not every protein source is equal

Different protein sources stimulate muscle growth differently, depending on the ’protein quality’ of the source. ‘Protein quality’ refers to how many amino acids in a certain protein source your body can actually harvest.

The first component of protein quality is the amino acid profile of the source. The second component is digestibility.

We’ve seen that a balanced amount of essential amino acids (EAA) is important, but it’s also important how easily the body digests these EAAs to end up in the bloodstream, readily available for muscle growth.

Protein quality: digestibility (and absorption)

Note: Digestibility means how well food gets broken down into smaller parts by chewing and processing in the stomach and intestines. Absorption is the actual uptake of amino acids, glucose, fatty acids, and vitamins and minerals from the digestive tract into the blood.

However, in this article we simply refer to the entire process – from foods to amino acids in the blood – as “digestibility”.

In general, your body digests animal protein sources easily (Tap) [2]. It’s harder to digest plant protein sources and extract their amino acids, since plant foods contain many anti-nutrients (Tap). Anti-nutrients interfere with digestion of the nutrients in a food.

Extra info: Anti-nutrients and evolution

From an evolutionary perspective, anti-nutrients protect a plant’s seeds from being destroyed by the digestive tract of animals, so a toilet visit can give a seed a new location, along with the soil it needs to grow. (Plants grow best in cow dung, remember?)

We call the seeds of a plant “grains”, which we can categorize into cereals and legumes. Grains have a very clear purpose: to store nutrients that make the plant grow, such as proteins.

Back in the day, grains with more anti-nutrients were much less comfortable for animals to digest. (Unless you think your farting from your kidney bean meal at your parents in law’s place is comfortable.)

Because of this, animals didn’t eat a plant’s seeds as often and these plant species survived until this very day.

And indeed research shows that (soy)beans [2], peas, cereals, and nuts all digest poorly (Tap). Specifically, walnuts, almonds, cashews, pecans, and pistachios contain fewer digestible calories (and protein) than shown on the nutrition label (Tap).

Furthermore, anti-nutrients also make vitamins and minerals harder to digest [2].

In general we could say that protein digestion is ~23% better on a meat-based diet compared to a plant-based diet (Tap) (Tap) [2]. Researchers prefer to assess this in growing pigs or rats when it’s very difficult to assess in humans.

In other words, eating mostly *whole plants* makes you digest 15-30% less of the protein on the food label.

Take-home messages:

- Technically, ‘grains’ are the seeds of plants, and come in the form of cereals and legumes.

- From an evolutionary perspective, anti-nutrients protect plant seeds (grains) against animals who want to eat (and digest) them.

- The human body can digest amino acids from animal products ~20% better than whole plant protein sources, leading to more amino acids in the blood per amount of food.

Protein quality: amino acid profile

Next to being harder to digest, plant-based protein also doesn’t have the same variety of protein building blocks as animal protein. As mentioned before, we call this ‘variety of protein building blocks’ the amino acid profile.

Since your body needs all essential amino acids to build muscle, you need to eat enough of every EAA for optimal muscle growth. When any single EAA is missing, this can halt muscle building (Tap) [2] (Tap).

You can compare constructing a muscle to constructing a fence: if some planks (amino acids) are smaller, it limits its total functional height (muscle growth): the neighbor can still peek over and overlook your private activities.

Plant-based foods often lack 4 specific essential amino acids, and we’ll focus on those in particular. Let’s call them ‘the big 4’: leucine, lysine, methionine and cysteine.

“But I thought cysteine was a ‘semi-essential’ amino-acid?”

Note that cysteine is technically not an ‘essential’ amino acid, but rather a conditional or ‘semi-essential’ amino acid. Your body can produce cysteine when sufficient methionine is available [2]. Basically, it ‘uses up’ methionine to produce cysteine, and you still want to eat enough cysteine to prevent ‘sacrificing’ too much methionine.

Food sources of ‘the big 4’ amino acids: leucine, lysine, methionine, cysteine

First, let’s look at how much protein various protein sources have per 200 kcal. Why per 200 kcal? Well, for instance, you can get 23 g of protein from 100 g of cheddar cheese. Sounds like a great protein source, right? However, you will then also ingest ~400 calories. Not so great; to get 150 g of protein per day, you’d need to eat at least 2500 calories. Basically, the graph beneath indicates how lean a protein source is.

The following graphs give an impression of which protein sources contain most of the big-4 amino acids. “Net” amino acids refers to the amino acids that actually end up in your bloodstream after digestion, which can be far less for some plant protein sources.

It’s important to note that we deducted the “optimal” amount of lysine, methionine, and cysteine from assumptions about a typical omnivorous diet, which you can read more about in the section “De-constructing the optimal protein intake”. There is no clear evidence that these are indeed ‘optimal’, but they give us an idea of how much we need for maximal muscle growth.

Also note the following things:

- Already you can see how combining certain protein sources or supplementing single amino acids can offer solutions.

- Unprocessed plant proteins, like lentils, have lower digestibility, than highly processed plant protein powders.

Notes on soy products and hormones

For vegans, soy protein isolate is probably the highest-quality protein source, together with blended protein powders (rice/pea for example). However, many people have the idea that eating soy products affects their hormone levels.

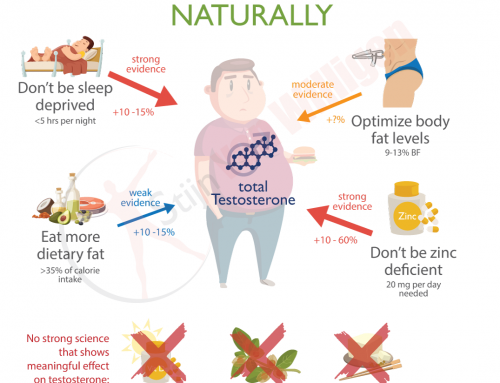

Overall, research shows that eating soy products doesn’t significantly affect testosterone [2] (Tap) or estrogen (Tap). As long as you’re not brushing your teeth with soy milk or eating 10 pounds of tofu per meal, you should be fine.

Furthermore, overall research shows that a soy-rich diet may help prevent cancer in women (Tap) (Tap).

Take-home messages:

- The anti-nutrients in plant-based protein sources make them harder to digest, compared to animal protein, which means you need to eat more of them to get the same amount of amino acids in your system.

- You likely need to ingest enough of every essential amino acid (EAA) to optimize muscle growth, which is why the amino acid profile of a protein source is important.

- Plant protein sources often have low amounts of the amino acids leucine, lysine, methionine, and cysteine. Therefore, we call these the ‘big 4’ lacking amino acids.

- We deducted the “optimal” amount of lysine, methionine and cysteine from assumptions about a typical omnivorous diet. There’s no solid evidence these are optimal.

- Research shows soy products do not affect testosterone or estrogen levels in any meaningful way.

Extra info: Why amino acids need to be optimal per meal, not per day

As you can see, we show the aminos in reference to the net optimal amino acids per meal, and not per day.

We know for certain that breakfast should contain enough of all the essential ‘big 4’ amino acids to maximize muscle growth (Tap).

However, some (scientists) argue that you only need to watch the total amino acid intake per day, and not per meal. They say the body can compensate for any lacking amino acids through a leftover ‘pool’ from an earlier meal (Tap), or can synthesize lacking amino acids when in serious need.

In serious need. Meaning malnutrition.

How about in serious need of maximum muscle growth?

We believe that in this case you do need enough net amino acids on a per-meal-basis, and this is why:

- Rats that consumed a supplement that lacks certain amino acids grew less muscle (Tap).

- Pigs grow more muscle when they consume a lysine supplement with every meal – to compensate for a lack in lysine – rather than consuming a lot of lysine once per day (Tap).

- In humans, supplementing with a small dose of whey/casein protein (<25 g) grows about two times as much muscle as a small dose of soy protein, which lacks leucine and methionine (Tap) [2, 3] (Tap).

- In humans, supplementing with a big dose of whey protein (>25 g) grows a similar amount of muscle as supplementing with a big dose of rice protein or soy protein [2, 3], as long as the big-4 amino acids amounts are optimal.

- Upping a dose of wheat protein from 35 to 60 g similarly stimulated short-term muscle growth as 35 g of whey protein.

So despite ‘a pool of leftover amino acids’, the research shows that if net amino acids per meal are not optimal, muscle growth is not optimal.

We can argue that we need to get enough of all essential amino acids per day, but also per meal, to maximize muscle growth. This is especially true for breakfast, after an overnight fast of 8+ hours.

Take-home messages

- There is confusion whether we should look at amino acid intake over an entire day, or on a per-meal basis.

- A theory exists that says the human body has a ‘pool’ of amino acids always available, which would make ‘timing’ of amino acids per meal irrelevant for optimal muscle growth.

- Multiple research studies in animals and humans indicate amino acid intake per meal is indeed important, especially for the serious athlete.

De-constructing the optimal protein intake

Before we can make any practical recommendations on how to solve the protein quality problem, let’s first look at how many individual amino acids a natural trainee (Tap) needs for optimal muscle growth.

Luckily, Menno Henselmans took all existing scientific data together and wrote a great article which concluded that the optimal amount of protein to consume is 1.8 g per kg of bodyweight per day (0.82 g/lb bodyweight), which translates to a certain ‘optimal’ total amount of individual amino acids.

Recent research supports the 1.8 g/kg figure (Tap). This is much higher than the RDI suggestion of 0.8 g per kg, probably because the latter doesn’t take muscle building into account. To build muscle we need to eat more of all the amino acids.

The best diet for growing muscle is high in protein, split into 3-6 meals per day [1], with 20-40 grams [2] (Tap) of protein per meal (Tap). However, total daily intake is more important than how you spread this out over your meals (Tap). Finally, you can benefit from eating a lot of protein before going to sleep (Tap).

To lose fat and maintain muscle, there’s no research that shows anything above 1.2 g/kg (0.55 g/lb) is beneficial (Tap). However, since eating up to 1.8 g/kg protein has an anti-hunger effect (Tap), we still recommend aiming at the high side when fat loss in your goal. Moreover, from experience we know that when going to very low (bodybuilding-like) body fat levels, this higher protein intake may be beneficial as well.

However, all the above research is based on omnivorous diets: the participants mostly ate animal products to get their protein in. Things change when you tend to eat more plant-based protein sources, as they are harder to digest and their amino acid profiles are different.

We went on to reverse-engineer the recommended 1.8 g/kg protein intake for a typical person of 80 kg into the total amount of every big-4 amino acid. For practical reasons, we assumed their main protein sources were chicken (25%), beef (25%), eggs (25%), and dairy (25%).

Finally, we split these up into 4 equally sized meals to get the theoretical optimal amount of leucine, lysine, methionine and cysteine per meal. See the illustration below.

Therefore, let’s look at 3 solutions for getting in all those amino acids for optimal muscle growth, without having to eat over 300 g of plant-based protein per day:

- Improving digestibility

- Combining (plant) protein sources

- Supplementation

3 solutions to non-meat optimal protein intake

Improving digestibility

Your body has a hard time digesting the amino acids in raw plant foods due to things like anti-nutrients. Fortunately, modern technology enables us to strips these foods of such anti-nutrients, while conserving all the amino acid goodness we want in our system.

How, you may ask?

Food processing.

For example, soybeans undergo multiple processing phases, through which they can end up on your plate in different forms. See the image below.

Yes, you can also improve the digestibility of plant protein sources at home. However, the reward-to-effort ratio is not very high. As you may recall, protein digestion is ~23% better on a meat-based diet compared to a plant-based diet [2], which means we can maximally improve digestion by ~20%.

By soaking, cooking, fermentation and germination you may be able to increase protein digestibility substantially. For example, actively soaking soybean flour for 9 hours will increase digestibility from 60 to 68% (Tap).

However, these studies didn’t investigate the digestibility in humans, but in test tubes (“in vitro”), which makes it even more uncertain whether spending 9 hours in the kitchen is worth anything at all.

I’d rather outsource those hours of processing to professional food manufacturers. But that’s me. In other words: give me that processed tempeh, tofu, and soy protein powder, because I ain’t got the time to ‘process’ it myself.

All in all, we can probably improve digestibility of plant protein sources, but doing it ourselves becomes a little impractical. Rather, we could let food manufacturers do this for us.

Buy those beans pre-cooked. Enjoy your plant protein powders.

Combining foods to get a better amino acid profile

To combine certain protein sources is another way to overcome the problem of lacking amino acids per meal. In this case, we have more influence.

For example, pea protein (powder) is high in lysine, but low in methionine and cysteine. On the other hand, rice protein (powder) is high in methionine and cysteine, but low in lysine. Therefore these two make a great combination when you blend them together, even rivaling the protein quality of beef.

When you eat eggs and dairy, you’re in luck: they greatly combine with plant-based foods to reach an optimal amino acid profile per meal. For example, eggs have a lot of methionine, and dairy has a lot of lysine and cysteine. These can complement a soy-based meal.

Supplementing lacking amino acids

So far we’ve talked about combining protein powders and adding eggs and dairy to get enough of ‘the-big-4’ per meal. However, if you don’t eat eggs and dairy, downing a pound of tofu for an optimal amino profile is probably not something you’re looking forward to.

By ‘filling up the amino acid gaps’, certain supplements can minimize the amount of protein you need to eat to reach optimal amino acids per meal.

For example, adding 500 mg of a methionine supplement, and 1000 mg of a lysine supplement to a tofu-based meal can drastically lower the protein you’d need to eat to get your optimal amino acids in, which is especially helpful if you want to eat less calories to cut body fat.

Take-home messages:

- Processing plant foods can increase their digestibility by up to 20%.

- Processing them yourself by soaking, cooking, sprouting, fermenting and such is very time-consuming, with only a small improvement in digestibility.

- Manufacturers are much better at this, so for practical reasons you want to leave the processing to them, and buy your ready-to-eat ‘processed’ tofu, tempeh, and protein powders in the grocery store.

- Some foods lack certain important amino acids, which other foods can compensate for. Intelligently combining them into a meal can decrease how much protein you have to eat for similar muscle building effects as animal protein.

- You can also fill these amino acid gaps with specific amino acid supplements, such as lysine and methionine capsules, which you take with your meal.

Conclusion, calculator and practical examples

Plant-based protein sources are generally harder to digest than animal protein sources and they lack some amino acids important to muscle growth. Therefore we need to think intelligently about how to set up a low-meat diet.

There’s a certain optimal amino acid amount per meal that guarantees maximal muscle building. Note that considering total amino acids per day is enough if you’re looking for general fitness and health, but you’re missing out if you’re a serious athlete trying to optimize everything. A video by Jorn Trommelen, a world-renowned protein researcher, confirms this.

There are multiple solutions to the plant-protein problems:

- Improving digestibility

- Combining protein sources for a better amino acid profile

- Supplementing lacking amino acids

You can improve digestibility simply by focusing – to a certain degree – on manufacturer-processed plant protein sources, like tofu, tempeh, meat replacements, and protein powder, which are stripped of a lot of the anti-nutrients that normally inhibit digestion.

If you intelligently combine protein sources within a single meal, you can elevate the amino acid profile to be similar to a meat-based meal.

Taking amino acid supplements with a meal can fill up lacking amino acid gaps, and save a lot of calories that would otherwise be spent on eating more of the plant protein source for sufficient amino acid intake.

The newest research actually shows protein quality may not be that much of an issue after all.

- A huge study of several studies (meta-analysis) showed soy supplements are equally effective as whey supplements for muscle and strength gains (Tap).

- A 2019 study found eating 1.6 g/kg of protein from plant sources – compared to animal sources – was equally effective for muscle and strength gains in beginners who only trained their quads and glutes (Tap) (Tap).

In light of these new findings, we’ve lowered the usual plant-based protein recommendations for muscle growth, as you can see from the image below.

To assess whether you have optimized amino acid intake per meal, you can use the calculator below. If you intelligently combine protein sources, you may need to eat a lot less total protein to reach optimal amino acids for muscle growth. See the image below.

Calculator

Use the following calculator to assess which amino acids may be lacking in your meals. Then refer to the earlier infographic to see which protein sources you need to add to your meals to complement the lacking amino acid.

Examples of optimized meals

Vegetarian meals

With the calculator at hand, here are some examples of tasty recipes that intelligently combine protein sources. A great tip for vegetarians eating dairy is to create sauces based on high-protein quark or greek yogurt, and add it to their plant-based meals.

For example, adding garlic to low-fat Greek yogurt (or quark) turns it into ‘hi protein garlic sauce’ that resembles aioli or tzatziki. The following recipe from our software/app incorporates it.

Vegetarian shoarma salad (tap for instructions)

Preparation time: 5 minutes

Calories 600 kCal

Protein 39 g

Fat 25 g

Carbs 55 g

Ingredients for 1 serving:

- 1 Tomato

- 200 g Lettuce, mix

- ½ tsp Garlic powder

- 150 g Morningstar chik’n strips

- 100 g Quark Elli, plain or vanilla, non fat

- ¼ Avocado

- 2 Bread, slices

1. Heat very little oil in a skillet on medium-high heat and stir-fry the chickenstrips for 4 min.

2. Meanwhile, slice the tomato and avocado.

3. Mix the garlic powder with quark, mix all other ingredients, top with the ‘tzatziki’.

4. Top the slices of bread with the salad and fold.

Basically, you can substitute the Greek yogurt for mayonnaise in any dish. Blend it with sriracha sauce to get ‘high protein sriracha mayonnaise’. Blend it with peanut butter (powder) to get a ‘high protein nut sauce’. The possibilities are endless!

Furthermore, eggs perfectly complement Asian dishes, such as this Indonesian tempeh dish.

Crispy tempeh noodles (tap for instructions)

Preparation time: 10 minutes

Calories 604 kcal

Protein 39 g

Fat 22 g

Carbs 63 g

Ingredients for 1 serving:

- 200 g Vegetable mix (chinese)

- 1 tsp Garlic powder

- 1/4 tbsp Butter

- 100 g Tempeh

- 50 g Egg noodles, uncooked

- 1 Egg (medium)

- 2 tbsp Thick soy sauce, manis

1. Bring water to a boil.

2. Cut the tempeh in pieces or strips with a thickness of max. 1/5th of an inch. Put them in a bowl (not on a plate) and heat them in the microwave (700 W). As a reference point, stick to 3 minutes per 100 g tempeh used, or until the tempeh gets crispy. Make sure to keep flipping the tempeh.

3. Meanwhile, heat butter in a big pan or a wok on medium-high heat. Stir-fry the vegetable mix, garlic powder and egg with 1 tablespoon of soy sauce for 5 minutes.

4. Meanwhile, put the noodles in the boiling water for 4 minutes.

5. Flip the tempeh in the microwave once and heat again until crispy. Keep 3 minutes per 100 g of tempeh used as a reference point.

6. Put the vegetable (sauce) from the pan on a plate. Heat remaining soy sauce in a pan on low heat. Stir-fry the tempeh in the pan for 1 more minute.

7. Drain the noodles, and serve on a plate along with the vegetables and the crispy tempeh with the soy sauce.

Tips:

– Use sambal to add spice to the meal.

– Use fresh garlic or mashed garlic instead of garlic powder.

– Season the vegetables with ground cumin.

– Sprinkle fresh coriander over the meal.

– Bake the tempeh in a pre-heated oven at 190 Cº for 20 minutes.

If other people eat along, serve 125 g of noodles per person.

Finally, cheese is a great compliment to an Italian tomato-pasta with meat substitutes. Definitely try this one out.

Vegetarian meatball pasta (tap for instructions)

Preparation time: 5 minutes

Calories 618 kCal

Protein 37 g

Fat 17 g

Carbs 71 g

Ingredients for 1 serving:

- 200 g Vegetable mix (Italian)

- 0.5 tsp Garlic powder

- ½ tbsp Olive oil

- 100 g Meatballs (meatless, Gardein)

- 75 g Pasta, fresh

- 2 tbsp Parmesan cheese

- 200 g Tomato basil sauce

1. Bring water to a boil in a pot, cut the meatballs in half.

2. Heat the oil in a large skillet on high heat, and stir-fry the meatballs for 1 minute.

3. Add the fresh pasta to the boiling water and cook for 4 minutes.

4. Stir-fry the vegetables in a skillet for another 3 minutes before adding the pasta sauce for another minute, finally adding the garlic powder, and salt and pepper to taste.

5. Drain the pasta and mix with the sauce, add the cheese on top.

Vegan meals

Vegans have to make a little more effort to get optimal combinations. As a rule, legumes (nuts, beans) combine greatly with ‘typical carb sources’ or derivatives thereof, such as seitan. Take for example the typical vegan bowl with lentils (beans) and quinoa (carb source).

Lentils severely lack methionine, but quinoa makes up for that. However, a better choice would be seitan, a gluten protein that contains a lot of methionine.

Vegan lentil and seitan bowl (coming soon)

Coming soon…

And finally, this is one of our favorites: fluffy pancakes with a perfect blend of rice and pea protein. You can make these bad boys in a matter of minutes, and they’re even better with erythritol (a crystallized sugar replacement) or low calorie maple syrup (Walden farms). The Sciencebakes pancake batter (10% discount here) contains chickpea flour (high in lysine) and wheat protein (high in methionine) for a great amino acid profile, which you can use instead of the soy protein powder wheat flour.

Vegan fluffy protein pancakes (tap for instructions)

Preparation time: 5 minutes

Calories 603 kcal

Protein 49 g

Fat 30 g

Carbs 42 g

Ingredients for 1 serving:

- ½ tsp Baking powder

- 50 g Soy protein powder

- ½ Apple (medium)

- 40 g Wheat flour

- 2 tbsp Olive oil

- 270 ml Water

1. Keep one third of the olive oil aside for later frying.

2. Combine soy protein powder, wheat flour, baking powder and olive oil and mix well, and add extra salt to taste. Afterwards, add water little by little to prevent the mixture from lumping together.

3. Cut the apple in slices of roughly 3 mm.

4. Heat up a small amount of oil in a frying pan at medium-high heat. Spread the batter in the pan and coat it with the apple slices. Bake for 3 min. per side or until it’s golden brown.

So we hope you now have enough knowledge (and recipes) at hand to tackle less-meat (or meat-less) lifestyle. If you’ve become interested in animal suffering due to the current state of the animal agriculture industry, Stijn highly recommends the book Eating Animals.

Be happy!

What about the research that methionine deficient diets can prolong life and have anti-cancer effect?

Hi Lipa,

Very good point. There are recent indications (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30725409 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29733806) that a methionine-restricted diet could inhibit the growth of cancerous tumors. Since a typical (without smart food combinations) vegan diet lacks methionine, such a diet could indeed potentially be beneficial for cancer patients. More research on that to come in the upcoming years, I hope.

And indeed, there are also indications that it can enhance life span (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5008916/). Together with the fact that vegan diets have now been shown equally effective for muscle growth at 1.6 g/kg BW as a meat diet (https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2019/06001/Does_Exclusive_Consumption_of_Plant_based_Dietary.2367.aspx#pdf-link) we should keep a close eye on what research finds next.

Until that time, for those looking to optimize muscle growth I advise to increase methionine intake on a vegan diet.

This is great! Thank you! One of the biggest questions we get from clients is how to bulk on a vegan diet, and this guide is going to allow us to answer that question so much better 😀

Thanks Shane, glad to hear it helps you and your clients!

Enjoyed reading this and will re read too what do you suggest for those of us who are vegan but also gluten free to maximise methionine, particularly to optimal amount ?

Hey Jo,

Thanks! That’s a tricky situation. I recommend highly depending on rice and soy protein powder, since seitan is not an option then.

Hi Stijn,

excellent material again! Many thanks for sharing your great stuff with us!

I have one question after reading the above article, you wrote that combining pea protein (powder) with rice protein (powder) makes a great combination when you blend them together.

Looking at your amino acids graphs however (which are GREAT!), could one also choose to go for soy protein powder as that seems to score well on all of the the ‘big 4’ amino acids?

Hey Aart-Jan,

Thanks. Sure you could go for the soy powder. It scores highly because it is relatively so low in calories per X grams of protein. Still; percentually it lacks methionine. But indeed soy protein powder is a great option as well.

Looking at the charts, wouldn’t soy + rice be better combination, as soy seems to be better or equal to pea for all EAAs? If so, which percentage soy vs rice would you reccommend?

Valid point. I’m not sure of the reason you don’t typically see this blend.

[…] CONTINUE READING HERE. […]

Hey, great article!

There is this high protein flour I use to make roti breads.

For the serving size I eat in one meal, it is P45 C35 F5

The ingredients include Isolated Wheat Protein, Pea Protein, Whole Oats, Amaranth Grain, Flax Seed Meal, FOS, Black Rice, Dried Jackfruit, Psyllium husk.

They dont print the per ingredient quantity /protein content.

Would the 50 g protein in that meal would be enough to not require supplementation at all?

Would adhoc supplemention with Lysine 1 g and Methionine 500 g to ANY vegan meal suffice or a more specific supplementation plan would be suggested?

Thanks, Yash.

Looking at the blend from wheat and pea protein, it probably has a decent amino acid profile, and you should be safe. However; without knowing the exact percentages you cannot really be sure.

You could add supplementation to ANY meal if you really, really want to be sure you hit your amino targets. But the evidence is not there to support it’s truly necessary. Your call.

Is there any science showing the effects of supplementing individual EAAs? To me that seems like the easiest approach, but I’ve read elsewhere that there is no studies showing that it actually works.

Also, do you have a specific comparison showing how much rice/pea blend powder you have to eat to get the same effect as approx. 30g whey?

Thanks for a fantastic article!

Thanks Victor.

The only evidence I know of is in animals, which I outline in the article section “Extra info: Why amino acids need to be optimal per meal, not per day”

Here’s an excerpt of what research finds:

Rats that consumed a supplement that lacks certain amino acids grew less muscle (Tap).

Pigs grow more muscle when they consume a lysine supplement with every meal – to compensate for a lack in lysine – rather than consuming a lot of lysine once per day (Tap).

Hi Stijn,

Great article!

I have a question about your calculator though.

In the final graph “optimal protein for muscle growth” you recommend 2,4 g/kg of protein for vegans and 1,8 g/kg for omnivores. However, If I fill in my weight in your calculator, 55 kg, it says 87,3 gram of protein as optimal. As the calculator is about combining protein sources, I would assume this 87 gr total is meant as optimal for a 55 kg vegan? How come this is not even 1,6 g/kg, even less then 1,8 g/kg for omnivores recommendation. So I was wondering what am I misinterpreting here?

Thanks again!

Wendy

Thanks, Wendy. Indeed, it’s the optimal *omnivore* protein amounts. The calculator then tells you how many of the different amino acids are in this amount of meat-based protein, and then lets you know what amounts of plant based proteins you should eat to hit those amino acid targets.